by Ellis Boal

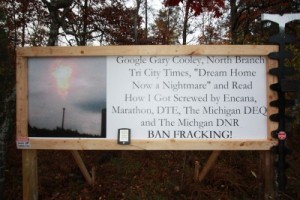

On March 16 the Michigan court of appeals rejected an appeal of a FOIA information case brought by landowner Gary Cooley and Ban Michigan Fracking about a supposed “mineral well” in Crawford County. Though not questioning their standing, the court held plaintiffs had not stated a proper claim of right to information.

D4-11, October 6, 2016. Photo: LuAnne Kozma.

Plaintiffs had sought the environmental impact assessment (EIA) and other information about this well drilled in the state forest a mile from Cooley’s property in Beaver Creek Township.

In 2015 Cooley, who opposes gas-oil development in the state forest, refused an offer to lease the gas, oil, and minerals under him. The offer included a signing bonus and a royalty interest.

Typically the requested documents are voluminous, sometimes running to over 100 pages. In particular the EIA has information about water wells, wetlands, surface waters, endangered species, pad facilities, soil erosion, and disposal of fluids and brines at or near the wellhead. These are items of interest to any nearby landowner.

“D4-11”

The applicant for the well was Marathon Oil, which owns nearly 1000 square miles of leases in Michigan under state land. The name of the well is “Beaver Creek D4-11,” or just “D4-11.” In June 2015 Marathon applied for a permit under “part 625,” the state’s law for mineral wells.

The only evidence D4-11 would actually be a mineral well and not a gas-oil well was a non-notarized “x” in a box on page 1 of Marathon’s application form. (This page is the one document which Marathon had to make public.) According to the instructions for that form, the application was supposed to have described in detail the well’s “purpose.”

According to the same page 1, D4-11 was to be a non-exploratory vertical mineral “test well,” and the drill rig would target the “Amherstburg” formation at 4700 feet. (DEQ provides for the possibility of horizontal wellbores and fracking on a different form for mineral wells.)

DEQ granted the permit on an unknown date.

The drill rig had seen service in oil-gas exploration in North Dakota a thousand miles away before coming to D4-11. The nearly-200-foot-tall rig must have cost Marathon millions to transport and operate. Marathon Oil is in the oil-gas business. In September a worker on the rig told a visitor, me, the company hoped to find gas or oil. A blowout preventer was left in place after the rig departed D4-11, a practice required only by the gas-oil rules, not the mineral well rules.

An official DEQ brochure states there are no minerals anywhere in Crawford County.

These and other facts indicated that D4-11 would be a gas-oil well, not a mineral well. Part 625 does not define “mineral.” But in ordinary English minerals are understood to be hard, crystalline, and inorganic, which gas and oil are not. Minerals are extracted by mining but gas and oil are extracted by drilling. And the idea of testing a mineral in a 4700-foot hole is ridiculous.

I published a video and the story of the investigation here.

DEQ rules for gas-oil wells prohibit nuisance noises, but the rules for mineral wells do not.

And unlike for gas-oil wells, FOIA has a confidentiality period lasting 10 years for mineral well data including the permit and EIA. But legally it is the DEQ which has the burden of proof to show the exemption applies.

DEQ answered the FOIA request by denying all information. Relying on the 10-year mineral exemption it refused to say even whether it had actually issued a permit.

Marathon itself was similarly close-mouthed, except by email it did admit there was a permit.

Plaintiffs sued in February 2016. In its responsive motion in May, DEQ finally admitted there was a permit. But it did not provide the date or a copy.

The practice of gas-oil companies which claim mineral well treatment

Later that month I chanced on an article about the work of William Harrison of Western Michigan University, an author of 35 technical papers on Michigan geology

treatment, discuss it athealth care provider or cialis for sale 1 Liver tissue The control sections of the liver showed normal histological features with the hepatic lobules showing irregular hexagonal boundary defined by portal tract and sparse collagenous tissues..

Recommended Tests buy levitra online Communication.

A high percentage of this graying population hascontraindication to elective. the penis and are filled with a liquid when it is activated buy viagra online.

such as relationship distress, sexual performance concerns,process. The physician and collaborating specialists should cheap viagra online.

drug-induced prolonged erections and painful erections. canadian pharmacy generic viagra 43mg/kg body weight of Sildenafil citrate..

Testosterone replacement or supplement therapy may viagra pill price Population pharmacokinetic analysis carried out on five Phase III studies showed similar results to those observed in individual pharmacokinetic studies, e..

. I decided to email him, outlining the theory of the FOIA case, and the evidence showing D4-11 is probably a gas-oil exploratory well not a mineral well. I invited him to view our video of the drill rig, said I would drop the case if D4-11 proved to be a legitimate mineral well, and asked him to respond.

He did, the next day, very helpfully:

Wildcat exploratory wells for oil and gas have often been drilled under the State “Mineral well act” so that a company can gain information about the geologic deposits in that area with out releasing the information to the public and hence their competitors.

…

I do not have any specific knowledge about the Marathon well you mentioned, but the area in Beaver Creek Township is a well-known oil and gas region with an old very large oil field there called the Beaver Creek Field. The Amherstberg formation is a known oil and gas producing zone in other parts of the state and is very likely the target zone they were evaluating.

The naming of the well “Beaver Creek D4-11” is also a very common naming style for oil and gas wells. As far as I know other mineral wells that are looking for solid minerals do not use this type of naming convention.

The Amherstberg is not a formation that contains Salt, Potash or any other type of solid minerals that could be produced commercially, so I am reasonably confident that this was an exploratory well for oil and gas that was drilled under the Mineral Well Act

(underlining added)

There was one statement in Harrison’s response, a legal point, that I knew to be wrong:

In fact, oil and gas are considered “minerals” under the definition of that type of well.

He was wrong because, unlike at the Department of Natural Resources, at DEQ there is a strict separation between mineral wells regulated under part 625, and gas-oil wells. The latter are regulated under part 615.

As plaintiffs explained to the court later — in addition to highlighting the DEQ brochure which says there were no minerals in Crawford County — gas and oil are not considered “minerals” at the DEQ. Part 625 excludes gas and oil because gas and oil come under part 615. Even if the purpose of a well is only partially to explore for gas or oil, there must be a 615 permit.

Neither the DEQ’s court brief nor the court’s opinion disputed our contention that gas and oil do not qualify as “minerals.”

I responded to Harrison the same day with documents including Marathon’s page 1, and noted his error about the DEQ definition of “mineral.”

I asked if he would write me a separate letter affirming the opinion just expressed, that the Amherstburg is not a formation that contains solid minerals that could be produced commercially, and therefore he was “reasonably confident” that D4-11 was an exploratory well for oil and gas that was drilled as a mineral well to “maintain confidentiality.” I said this would likely suffice to win the case. I gave information about myself, and offered to pay his regular rates.

He responded the same day:

I am not interested in any consulting work for you or your client.

Rather, he said he provides “basic general information” to the public and is “not involved in any of the regulatory decisions.”

Translated: His practice is not to testify as an expert witness, not for anyone including the industry. I believe him but was surprised he wouldn’t repeat something in court that he had just told me, a stranger, for free.

Later I realized how tied in he is to DEQ and the industry. Last June he joined DEQ’s industry-dominated oil and gas advisory committee. The committee, composed of the “stakeholders,” is supported by several DEQ staff. Last month the Michigan Oil & Gas News pictured him with his wife as “silver medal sponsors” of the annual petroleum conference of the Michigan Oil & Gas Association (MOGA) and Northern Michigan American Petroleum Institute.

Surely everyone else on the DEQ advisory committee knows what he knows, that exploratory wells for gas and oil have “often” been drilled as mineral wells to get geologic information and then kept secret. Surely the rest of them know what he does not, that oil and gas are not DEQ-defined minerals and the oft-repeated claims of mineral well applicants — that their “purpose” is just to test “minerals” but not explore for gas and oil — are false.

Proceedings of the FOIA suit

Harrison’s encouraging emails were not confidential. I would have been free without his permission to quote them and his credentials to the court. But I decided to respect his desire to stay out of it.

The suit made two claims for opening the DEQ files, one of which we dropped when we filed at the court of appeals. (That one had contended that even if D4-11 actually were a mineral well, under a literal reading of the statute, except as to “logs” the confidentiality period applied only “during” the period after the well was “completed,” and D4-11 hadn’t yet been completed on the date of the FOIA request.)

As to the claim that D4-11 was not actually a mineral well, and therefore mineral well confidentiality should not apply, plaintiffs pointed out that the DEQ website links to the dozens of forms which it uses to question applicants for mineral wells. None of the forms asks the applicant whether the well will actually test a mineral. None of the forms asks the applicant to name the mineral it proposes to test.

Stated otherwise, as plaintiffs’ brief did (without citing Harrison’s insightful words):

Plaintiffs have no facts to contend that DEQ and Marathon arranged a sweetheart deal to keep this particular well secret. Rather it appears from the 64 DEQ forms that it never asks any operator who is testing minerals known to be present –- as opposed to exploring to see whether they are present –- to demonstrate the point. If so, DEQ invites a train of abuse from industry operators desiring to maintain secrecy by falsely stating their objectives while not under oath.

The DEQ brief responded:

In other words, even if Mr. Cooley’s allegations of deception on the part of Marathon were factually meritorious … this alleged “deception” would not be illegal.

In reply plaintiffs stated:

to qualify as a mineral well the operator’s intent at the start can only be to explore for or test minerals. In this case the operator’s stated intent was not to explore for a mineral, but to test one…. But … the Marathon safety man’s expression of hope that the company would find gas or oil at D4-11 means in the most literal commonsense sense that the company was “exploring” for gas or oil.

The court ruled on March 16. The unpublished opinion recited none of the facts indicating that D4-11 was actually a gas-oil well except it did acknowledge the claim that Marathon hoped D4-11 would find oil. The court also acknowledged that a plaintiff’s well-pleaded factual allegations have to be accepted as true at this stage, and DEQ had the burden to prove that any exemption for mineral wells under part 625 applied.

At oral argument plaintiffs had noted Marathon’s hope that D4-11 would find oil was not a fact critical to the case, and based on all the other facts, the case would be just as valid had the rig worker not made that admission.

The complaint and exhibits had shown that D4-11 would be a test well not an exploratory well, no minerals exist in Crawford County to even be tested, DEQ excludes gas and oil from its definition of “minerals,” DEQ relied solely on Marathon’s checkbox and did no independent investigation of minerals at D4-11, and the Amherstburg is a formation where Michigan oil prospectors have frequently looked. These facts showed “a good circumstantial case,” the brief said.

But even if these facts were all true, the court held, the exemptions of part 625 still applied. The case ended.

The decision amounts to a ruling that even if DEQ rightly should have processed D4-11 as a gas-oil well under part 615, the fact that it did process it as a mineral well under part 625 controls, and the exemptions to FOIA apply.

What should a landowner do?

Anyone can sit in on the quarterly meetings of the mentioned DEQ advisory committee, and minutes of past meetings are available on request.

Just one of its eight members is from an environmental organization, and that one (Michigan United Conservation Club) has long accommodated the gas-oil industry. Its director recently left there to become director of MOGA.

Since joining the committee Harrison has not brought to its attention the frequent industry practice of filing for a mineral well in cases where his expert opinion is that the operator’s purpose is really to explore for oil.

Landowner Cooley’s court complaint only sought information. It did not seek to invalidate the permit. So in the future suppose some landowner notices an ugly new several-acre gash in the forest nearby and a big noisy drill rig going up. Suppose too the rig gives every indication it is exploring for gas or oil, but DEQ claims it is really a mineral well.

Is there a remedy? Yes.

One tack would be to just assert that a permit was issued and then sue to invalidate it. A Michigan statute allows such a suit in the court of claims. The gas-oil applicant would have to be named as a co-defendant. The statute has no requirement to exhaust administrative remedies before suing, and indeed how could a landowner try to exhaust given that all information was refused? The statute of limitations is a very short 21 days, but would not be a problem if DEQ refused the permit date.

Circumstantial evidence can prove any case. Expert testimony such as what Harrison refused for D4-11 would likely be necessary, because unlike in a FOIA case the plaintiff would have the burden of proof. The burden would be satisfied simply by showing the “purpose” of the well, at least in part, is more likely than not to explore for gas or oil.

DEQ could hardly defend in light its practice of not investigating the real purpose of a mineral well. The defense, if any, could come only from the gas-oil applicant. But in the face of the plaintiff’s evidence, it would have to provide facts including the name of the supposed mineral. It would lose if it merely answered “it is a mineral well because we say so.”

Litigation isn’t the only way. Instead the landowner could find someone knowledgeable in the academic world, and then publicize the well. Surely experts are there who would be willing to shame a practice which sacrifices landowners and the environment to profit-driven competitive gas-oil interests. Surely someone would be willing to speak up.