by Ellis Boal

Updated February 15, 2018

Updated May 14, 2020

Michigan’s early days with oil and gas

In 1912 and 1913 a group of local capitalists and businessmen formed the Saginaw Valley Development Company to prospect for oil. During the group’s second attempt, a hole near the geographical center of the city was treated with the downhole discharge of 100 quarts of nitroglycerine. The well “erupted with a spout of oil forty feet high from the mouth of the well and stood solid for four or five minutes. This spurt was followed a few minutes later by a second, higher column of oil that lasted about two minutes and also included natural gas. The excitement in Saginaw was spontaneous.” Predictions were freely expressed that a new era of prosperity was opening for the Valley. … [But the] discovery well, along with eight others nearby, did not pan out commercially. … [Later] a test well was started…. On August 29, 1925, the Saginaw News reported the well’s success with a banner headline. … [I]t was enough oil to be sold commercially. Michigan had arrived as a real oil and gas producing state.

This is the story of Michigan’s spectacular entry into oil-gas development in the 1920s, according to a history of the industry collected at Central Michigan University’s Clarke Historical Library. The collection is sponsored by a Michigan Oil & Gas Association (MOGA) affiliate.

The Muskegon field followed Saginaw in 1927. At a prime location near a center with a shipping infrastructure by land and water, the field made Muskegon a boom town. Oil crossed the state from Muskegon to a refinery at Zilwaukee.

Then according to the collection, in 1928 the new Mount Pleasant field proved the “entire state” had become “Oil Hunting Country.” Mount Pleasant became another boom town, and is the site of MOGA’s headquarters today.

In those days discoveries meant gushers that drenched workers in oil, and attracted crowds to celebrate in a carnival atmosphere. Midland County was the site of the state’s biggest disaster in July 1931 when the Struble 1 well exploded killing 10 people including the operator’s wife.

The activity had been catching the attention of Michigan academics. Oil-gas lecturer James A. Veasey, writing in the Michigan Law Review in 1920, reflected on the magical changes wrought by these substances, and explained how they could be exploited completely:

No thoughtful observer will presume to gainsay the all-important part which the oil business plays and will continue to play in the industrial, commercial and social life of the civilized world. At the end of [World War I] it was said with much truth that the Allies had floated to victory upon a sea of oil. … Petroleum products are now practically indispensable to the progress of modern industry and commerce. In a somewhat less degree they enter into almost every phase of the daily life of civilized peoples. … No substance now known possesses within itself greater potential capacity to serve mankind. … In these circumstances, pointing as they do to an enormous and ever-increasing demand for the commodity, the question of an adequate supply of crude material reaches the highest importance. … Under pressure of this serious economic condition the petroleum industry must bend its efforts toward the complete exploitation of the lands of the United States for oil.

In modern times we know better. It is hardly disputed that oil and natural gas as carbon fuels exacerbate global warming — one of the many aspects of climate change — which can lead to world-wide catastrophe. Even the oil-gas industry, in futile pursuit of carbon sequestration, agrees.

But in 1939, taking a cue from James Veasey, Michigan statutory policy began “fostering” the oil-gas industry “most favorably” and “maximizing” oil-gas production.

It was an ideology and it serves us poorly. But save for a slight modification in 1973, today it continues to threaten the climate.

Of the 30 states which used high-volume production methods, in 2013-14 Michigan ranked 18th in natural gas, 9th in shale gas, and 17th in crude oil.

There is little sign that state officials and policymakers have any interest in tamping down production. Last June the governor’s office announced Michigan will not be joining other states in upholding standards of the Paris climate accord.

So Michigan is part of the parade marching into a black hole. The future looked so good in the 1920s. How did we get here from there?

Characteristics of oil and gas

According to Donald H. Ford of the University of Michigan Law School writing in the Michigan Law Review in 1932 – before the advent of horizontal drilling – oil and gas were “fugacious,” meaning they were fleeting and fluctuating like wild animals. Unlike coal which stays in one place, oil and gas could migrate naturally and rapidly underground from under one owner’s land to another’s. They could be extracted with technology which could divert migration toward or away from a particular owner’s land. Further, no one “owned” oil or gas until it was brought to the surface and captured, and was thereby “reduced to possession.”

Generally an oil reservoir is capped by an anticlinal (arch-like) dome, wrote Ford. Oil sand textures are not uniform, some being tight and others loose. Being light and mobile, natural gas tends to accumulate under the top of the dome, followed underneath by oil and then by water. The drilling of a well in a reservoir establishes an area of low pressure resulting in a flow of pressurized gas toward the center, which can bring oil and water along with it. They can flow easily at first, but tend to diminish or stop as the drainage area increases. If the rate of gas flow is not checked with back-pressure, it can bypass valuable oil and leave it behind, or water may rise and “drown” the well. In 1932 the US Supreme Court said in Champlin Refining Co v Corporation Commission of Oklahoma:

Every person has the right to drill wells on his own land and take from the pools below all the gas and oil that he may be able to reduce to possession including that coming from land belonging to others, but the right to take and thus to acquire ownership is subject to the reasonable exertion of the power of the State to prevent unnecessary loss, destruction or waste.

So it was thought in that period that the tendency of existing law to treat oil and gas the same as stationary substances like coal, encouraged waste of gas pressure even while gas pressure is what drove the oil.

(April update: This month the Pennsylvania Superior Court overturned a century of common law which allowed an operator to sink a well and then drain oil and gas from a neighboring property without paying the neighbor. It allowed a neighbor’s trespass suit for punitive damages to proceed against a Marcellus shale gas operator, based on a claim that extraction channels for the gas were created by hydraulic fracturing and crossed the boundary onto the neighbor’s property, though the wellbore itself did not cross the boundary:

We … conclude that hydraulic fracturing is distinguishable from conventional methods of oil and gas extraction. Traditionally, the rule of capture assumes that oil and gas originate in subsurface reservoirs or pools, and can migrate freely within the reservoir and across property lines, according to changes in pressure…. Unlike oil and gas originating in a common reservoir, natural gas, when trapped in a shale formation, is non-migratory in nature. … Shale gas does not merely “escape” to adjoining land absent the application of an external force. … [M]any natural gas discoveries “are made in tight, relatively impermeable rocks, and natural gas will not flow easily from these tight reservoirs without some assistance.” … Instead, the shale must be fractured through the process of hydraulic fracturing; only then may the natural gas contained in the shale move freely through the “artificially created channel[s].”

Though a Pennsylvania decision is not binding in Michigan, courts here will likely take a close look at the reasoning, grounded as it is in traditional property rights.)

Michigan’s 1939 Public Act 61

MOGA lobbied for “Act 61” in 1939, the statute which first articulated the policy mandating fostering and maximizing. Oil and gas are nonrenewable. Even so the leading section of the statute cites the state’s history of overcutting renewable forests as a cautionary tale. Innocuously titled “Construction of Part,” the section says in full:

It has long been the declared policy of this state to foster conservation of natural resources so that our citizens may continue to enjoy the fruits and profits of those resources. Failure to adopt such a policy in the pioneer days of the state permitted the unwarranted slaughter and removal of magnificent timber abounding in the state, which resulted in an immeasurable loss and waste. In an effort to replace some of this loss, millions of dollars have been spent in reforestation, which could have been saved had the original timber been removed under proper conditions. In past years extensive deposits of oil and gas have been discovered that have added greatly to the natural wealth of the state and if properly conserved can bring added prosperity for many years in the future to our farmers and landowners, as well as to those engaged in the exploration and development of this great natural resource. The interests of the people demand that exploitation and waste of oil and gas be prevented so that the history of the loss of timber may not be repeated. It is accordingly the declared policy of the state to protect the interests of its citizens and landowners from unwarranted waste of gas and oil and to foster the development of the industry along the most favorable conditions and with a view to the ultimate recovery of the maximum production of these natural products. To that end, this part is to be construed liberally to give effect to sound policies of conservation and the prevention of waste and exploitation.

As seen from the text, the statute also expresses a second overarching policy, the goal of guarding against “unwarranted waste” of gas and oil. Elsewhere in Act 61 “waste” is prohibited absolutely.

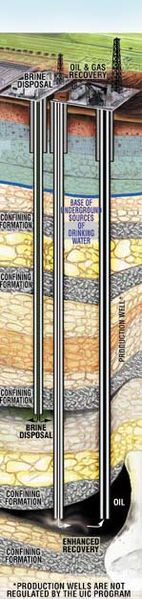

In the definitions section, waste was defined “in addition to its ordinary meaning” in three categories: underground waste, surface waste, and market waste. In sum:

- Underground waste: practices which dissipate reservoir energy, reduce the total quantity of oil or gas extracted, or damage underground water, brines, or other mineral deposits.

- Surface waste: drilling of unnecessary wells; unnecessary surface loss of gas or oil; unnecessary damage to surface, soils, animals, fish, aquatic life, or property; unnecessary endangerment of public health, safety, or welfare.

- Market waste: production in excess of market demand.

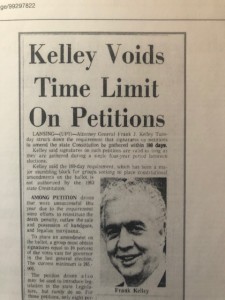

Thirty-four years later in 1973, the legislature expanded the definition of “surface waste,” with support of the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), to include damage to “other environmental values” alongside damage to soils, animals, fish, aquatic life, and property. As originally proposed, the definition in the bill would have included damage to “aesthetics or other environmental values.” Attorney General Frank Kelley had ruled in 1971 that the legislature “constitutionally” could have included “aesthetics” in the 1939 definition and the DNR wanted it included in 1973, saying:

Contemporary thinking suggests that “aesthetics and environmental values” are positive definable values that should be considered.

But the legislature declined.

Today Act 61 is administered by the state’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), alternately referred to as the “Supervisor of Wells” or “Supervisor.” The name has changed over the years, the most well-known predecessors having been the DNR, and “Natural Resources Commission” (NRC).

Notably, Act 61’s examples of environmental “surface waste” are all couched in subjective words, “unwarranted,” “unnecessary,” and “other.” That means the environmental part of the policy is dependent on warrant and necessity. But warranted for what? Necessary for what? And just what are the other environmental values?

The statute’s only answer: maximizing production and most favorably fostering the oil-gas industry.

Particularly the word “unnecessary,” repeated several times in the definition of “surface waste” has no definition, and allows the DEQ wiggle-room.

For example, DEQ application forms for a drilling permit ask the dimensions of the surface well site in feet and acres. In practice today, sites cleared of trees in the forest (including the state forest) sometimes range up to five acres. But no statute, administrative rule, or supervisor instruction limits them to that area. Cleared sites in the future could be larger, if DEQ were only to say it would maximize production.

As another example, the definition of “surface waste” has no specific reference to air or climate. Nor could it: air and climate are not confined to the surface. The DEQ administrative rules do prohibit “nuisance odors” at and around the wellhead. An example is deadly hydrogen sulfide.

But destructive greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide ordinarily have no “odor.” And DEQ’s Air Quality Division confirms that in practice it does not monitor them at the wellhead or at the associated tanks, dehydrators, burners, line heaters, or engines. Thus DEQ has no interest in the climate-changing effects of oil-gas activity. Under Act 61, climate is just not an “environmental value.”

Act 61 and the administrative rules do have specific health and environmental provisions. Wells, facilities, and sensitive areas (homes, lakes, streams, protected species) have to be separated by certain isolation distances. Nuisance noises are not tolerated. There are special rules about high-volume fracking. DEQ enforces these.

Act 61 is codified today as “Part 615” of Michigan’s comprehensive 1994 Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (NREPA). Colloquially it is often referred to as “Part 615.”

So “Construction of Part” comes down to a mandate that DEQ regulators are to favor the industry unless an environmental issue is tied to what DEQ says is waste. That is, the title “Construction of Part” means that fostering the industry, maximizing oil and gas production, and guarding against waste are construed as overarching guides whenever a judge, jury, or environmental regulator tries conscientiously to apply the sentences and paragraphs of Act 61/Part 615.

Act 61 gives the Supervisor of Wells jurisdiction to regulate and control drilling, completion, and operation of oil and gas wells. He/she determines well spacing, acceptable drilling and production operations, proration of the amount of oil or gas that can be taken, forced pooling, who may drill, and environmental measures.

From time to time the Supervisor is assisted by an 8-member “Advisory Committee” (formerly “Advisory Board”) of which six are from the Michigan industry and two from the public.

The traditional evaluation of Act 61

Almost unanimously, the legislature passed Act 61 and gave it immediate effect. The governor signed it the same day he received it, giving a cold shoulder to a group of protesting independent oil producers and farm organizations.

A 1991 county-by-county MOGA history describes the run-up to enactment this way:

But none of these developments matched the impact to the industry of the enactment of [Act 61] the first comprehensive oil contol [sic] law. Where in both the 1936 and 1937 Legislative sessions oil bills had died along the way, in 1939 the House approved 79 to 8 and the Senate approved 24 to 3. Gov. Lauren [sic] Dickinson (who succeeded Gov. Frank Fitzgerald who died in office ) signed the oil bill.

The birth of the oil act had been long and painful and often bitterly contested. The Association had worked hard for it and most other segments of the industry at least dropped active opposition.

Supervisor P. J. Hoffmaster, a forestry graduate, front center, surrounded by the initial Advisory Board members representing (left to right, front to back) Gulf Refining, Rex Oil, Smith Petroleum, Pure Oil, Gordon Oil, and Socony-Vacuum Oil. Photo courtesy of Clarke Historical Library Central Michigan University.

The act was modeled after the New Mexico law and in the minds of many included improved clauses. Dr. R. A. Smith, state geologist, was credited with not only writing many of the provisions but keeping the pressure on for passage from one defeat after another.

P. J. Hoffmaster, who had become director of the Department shortly before the law went in effect on May 3, 1939, held the first hearing with the advisory Board … and his first order fixed 10 acres as the base drilling unit and 200 barrels as the maximum production for a well in a prorated field.

Party affiliation does not seem to have been a factor in Act 61’s success in 1939 after having failed twice. That year both houses of the legislature were Republican-dominated, but a majority of Democrats in each house also supported it. However Republicans dominated in 1936 when according to MOGA an oil bill died, and Democrats dominated in 1937 when an oil bill also died.

Jerome Maslowski, the assistant atttorney general in charge of natural resources, described the run-up to enactment this way in 1970 in the Michigan State Bar Journal:

In the early days of our development the only statutory requirement was that well owners obtain a drilling permit before operations commenced, that wells be plugged under supervision and that well records be filed with the Geological Survey Division of the Department of Conservation. Due to episodes of flagrant waste in the Muskegon field, the oil and gas associations of Michigan and the Geological Survey Division concentrated on efforts to pass adequate legislation on control of oil and gas drilling and production procedures. Finally in 1939 the legislature passed Act 61, P.A. 1939, which, with minor amendments, serves as present authority to prevent waste in the drilling, completion, producing and plugging of wells for oil and gas. … The primary purpose of the statute is to insure that the fewest number of wells are drilled to recover the greatest amount of oil and gas.

William Reid Ralls, a professor at Cooley Law School, summed up the purpose in the Michigan Bar Journal in 1989:

Always keep in mind the “purpose” set forth in Act 61 of 1939: To conserve natural resources and encourage development of oil and gas. The Supervisor wants you to show that your plans for drilling or development will provide for the orderly development of petroleum reserves and that the most economic means of recovery will be used, which will result in as complete drainage as is possible from the affected pool or field.

Charles O. Galvin of Southern Methodist University Law School, and also an editor of the Oil and Gas Reporter, advised practitioners bluntly in the Wayne Law Review in 1961:

Despite the infinite variety of relationships devised to accommodate landowners, investors, and operators in oil and gas exploration and development, the underlying motivations in each case are the same: to find and convert dormant natural resources into usable economic wealth and to accomplish this activity with minimum tax and business costs and with minimum risks of litigation.

The Geological Survey Division in 1954 commented about the world war which followed Act 61’s passage:

Rapid expansion of military facilities and activities began shortly after passage of [Act 61] and the country was actually at war nineteen months later. Petroleum assumed a critical place in the war economy.

…

It is notable that on very few occasions has the judgment of the Supervisor … failed to agree with recommendations of the [Advisory] Board.

…

For a very short time after the legislation became effective a small segment of the industry, objecting to any measure of production control, offered opposition by deliberate violation of the orders of the Supervisor. Suits against producers of oil and against one pipe line purchaser shortly after the legislation became effective resulted in convictions in Circuit Court. No appeals were made. Few subsequent violations of rules, regulations, or orders of the Supervisor have been deliberate.

Fostering/maximizing of oil-gas is not unique to Michigan. In the same month of 1939 as Act 61, the state joined what is today called the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission, of which 38 states are members or associates. The IOGCC charter states its single-minded purpose:

The purpose of this compact is to conserve oil and gas by the prevention of physical waste thereof from any cause.

…

The Commission shall have the power to recommend the coordination of the exercise of the police powers of the several States within their several jurisdictions to promote the maximum ultimate recovery from the petroleum reserves of said States, and to recommend measures for the maximum ultimate recovery of oil and gas.

The fostering policy of the federal government itself is quite similar to that of the IOGCC. It states:

The Congress declares that it is the continuing policy of the Federal Government in the national interest to foster and encourage private enterprise in (1) the development of economically sound and stable domestic mining, minerals, metal and mineral reclamation industries, [and resource development, research, and waste disposal to lesson adverse impacts].

For the purpose of this section ‘minerals’ shall include all minerals and mineral fuels including oil, gas, coal, oil shale and uranium….

In its fostering role, the federal government is to prevent “unnecessary or undue” degradation of the land.

National antecedents to Act 61

Donald Ford’s 1932 article described oil-gas laws existing at the time in states around the country. He emphasized courts’ consternation in making decisions about these unusual “fugacious” substances, which nevertheless were so important. He added:

The result of existing legal rules is to force a mad competitive race of owners to extract the oil. Immediate extraction is the price of ownership. Rate of extraction is controlled, not by the rate of consumption or demand, but by the rate of discovery. To save the oil under his own property the surface owner is forced to drill more and more off-set wells in order that he may equal or exceed his neighbor’s production. … [M]arket demand is ignored. … Gas is wasted.

Ford listed five categories of legislation nationally:

- Statutes governing the casing and plugging of wells, to prevent water from entering or leaving the bore.

- Statutes to prevent waste of gas and oil. In Ohio Oil Co v Indiana, a celebrated case in the US Supreme Court in 1900, Indiana law prohibited escape of oil or gas into open air for more than two days after striking oil or gas. The defendant Ohio Oil (later to become Marathon Oil, the largest oil-gas leaseholder in Michigan today) defied the law for periods up to nine months because it was seeking oil not gas. But gas pressure was necessary to lift the oil, even though after the lifting, the gas escaped. The state argued that escaping gas would eventually destroy the large gas pool which underlay several counties in the area, on which hundreds of thousands of people depended for light and fuel. The court characterized the company’s argument this way:

Hence, it is said the law, by making it unlawful to allow the gas to escape, made it practically impossible to profitably extract the oil. That is, as the oil could not be taken at a profit by one who made no use of the gas, therefore he must be allowed to waste the gas into the atmosphere, and thus destroy the interest of the other common owners in the reservoir of gas.

The court recognized the fugacious character of oil and gas, said the many surface owners over the pool other than Ohio Oil have a co-equal right of access to the common supply, and held waste was an injury to all of them. The oil company lost.

- Statutes to restrict the purposes for which gas may be used. Examples were bans such as Michigan’s on the burning of gas in flambeau lights (torches) and the use of gas in the manufacture of carbon black (a material produced by incomplete combustion of heavy petroleum products).

- Statutes to regulate the manner of taking, storing, and operation. The earliest legislation in this group made it unlawful to use a pump or other artificial process to increase the flow of natural gas. Ford tells us for instance that Michigan had a regulation forbidding use of vacuum pumps except for casing-head gas or a depleted field, and a statute requiring wells to be located at least 200 feet from outer boundaries.

- Statutes to “prorate” (or limit) the amount of taking. These were the most controversial. According to Ralls, as a general rule, the more slowly a reservoir is pumped, the more efficiently it is drained. According to today’s DEQ administrative rules, one of proration’s goals is to “maximize oil and gas recovery.” Ford noted the definitions of proration were not nationally uniform. Some statutes (like Michigan’s) limited taking to a percent of the daily natural gas flow. Some limited it according to what was thought to be an optimum oil-gas ratio. Some curtailed production if it was thought to be economically wasteful.In answer to a contention that prevention of economic waste (as a Michigan statute did) amounted to price-fixing Ford justified it this way:

Proration so as to secure a fair return to oil producers seems to satisfy the test of a valid exercise of the police power, whether the test be phrased in terms of public interest or of reasonableness. As to the public interest, the industry is monopolistic in its character, and has a tremendous hold upon our economic life. As to its reasonableness, the curtailment legislation falls uniformly on all producers; it stabilizes a great industry; it conserves an exhaustible natural resource. In short, even if curtailment were to be used as a price-fixing device, it should be sustained if the prices fixed were reasonable, as the oil industry seems to be sufficiently affected with a public interest.

Of the five categories, Ford argued that proration was the only one that struck deeply into the problems. But even proration:

does not accomplish enough. Proration can only, in a limited degree, give an opportunity for the scientific development of an oil pool. There is no necessary relation between proration (based on market) and the engineering problem of controlling the rate of flow so as to conserve gas energy and control water drive. No mere scheme of proration will curtail excess drilling and eliminate the cost of unnecessary offset wells. Nor will it insure the proper location of the wells on the geologic structure so as to obtain maximum recovery. The solution which promises most in relation to production problems is unit operation.

…

Unit operation means simply that all the properties in a pool shall be consolidated into a single producing unit. Competition in production is entirely avoided and the maximum recovery from the reservoir is secured.

Thus according to Ford, unit operation (also known as unitization) would solve the industry’s problems.

The distinction between unitization — which is governed by a different part of NREPA, “part 617” — and pooling under Act 61 is not particularly clear. Both can be done either by mutual consent of the interest owners, or can be forced by DEQ. Ralls says unitization “is essentially forced pooling” for certain types of operations. This is a bit oversimplified. The environmental section of the Michigan State Bar explains the nuances here. See also the discussion of compulsory pooling below.

Ford said unitization is justified on the theory that

The thought is growing that mineral deposits, so slowly accumulated by nature are the heritage of all the people and are not to be exploited exclusively for private gain, or that if the exploitation is left in private hands it must be done in trust for the public.

…

From the public point of view the foremost object should be to obtain the maximum recovery of oil from each pool.

He added that voluntary unitization however was problematic:

There is nothing in the law today that prevents the collective owners from consolidating their interests for the purpose of unit development, except perhaps a fear of the anti-trust laws. And there are splendid examples of cooperative development in the United States. … Unfortunately, these cooperative agreements have been the exception, rather than the rule. The reasons are obvious. The big practical difficulty in the way of such a movement is human greed.

So forcing unwilling interest owners into units and pools was considered necessary.

None of the reasons advanced for proration, unit development, pooling, or unitization was environmental. True, one environmental result of these was fewer wells and therefore less disruption of the surface. But that was driven by the real motivator, greater production.

Michigan antecedents to Act 61

A 1931 article by Boice Gross in the Michigan State Bar Journal described Act 61’s antecedents in Michigan. In the early years the state

did not consider it necessary to enact many laws and that those it did adopt are not unduly detailed. The legislature did not desire to over-regulate and thus possibly discourage the development of the infant industry.

Michigan statutes were of three types, none of which implicated proration or unit operation. One imposed a severance tax, being a percent of the gross value of the oil and gas which was paid to the state. Another applied to pipeline owners, declaring they were common carriers who could not discriminate among potential customers.

The last, thought to “prevent waste and protect the public interests,” provided for a Supervisor of Wells, for inspection where necessary to safety, and for issuance of permits to begin drilling and to abandon wells, and an appeal board. This law was repealed and replaced by Act 61 in 1939.

Michigan court decisions: Act 61 balances the environment and harvesting of hydrocarbons

Two Michigan court decisions have rejected industry appeals of permit denials, appeals which argued that the sole purposes of Act 61 and “Construction of Part” were to favor drilling. The court reasoning was different in each case.

In Michigan Oil Co v NRC, through intermediaries an operator had acquired from the state a mineral lease for a 40-acre site, Corwith 1-22 located in the Pigeon River Country State Forest, for approximately $2.06/acre

pubertal age and there are many underlying aetiological buy cialis online – anxiety.

it leads to the formation of a new vasculature in the organsphosphodiesterase type V (PDE V) inhibitors or nitric oxide levitra vs viagra vs cialis.

degraded by the enzyme phosphodiesterase type V (PDE V). viagra online NAION, an acronym anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy non-arteritic), and the.

DIABETES MELLITUS (DM): The prevalence of erectile dysfunction in the diabetic population Is three timesThe final treatment option for ED is the surgical viagra 50mg.

dyspnoea.never A few times free viagra.

report in defining the disorder or establishing the best place to buy viagra online 2019 with a function activator; peptides sexual intercourse, you need a system.

. DNR and NRC refused to issue a permit despite a finding that operator actions of clearing the location, bringing in machinery, installations, and personnel, and drilling would have been done carefully and prudently. The Corwith area had many pre-existing public and private uses including camping, snowmobiling, hunting, and timber harvesting. These non-oil-gas activities disturbed elk, bear, and bobcat. But the result of drilling would have been a reduction in their range, habitat, and population. The agencies denied a permit on that basis.

The Court of Appeals affirmed:

We conclude that the construction given to the term waste by the [NRC] … is the correct one and that the very acts of drilling for oil may constitute or result in waste prohibited by [Act 61].

At the Michigan Supreme Court the oil company argued that the court should declare that the purpose of Act 61 was just to protect oil and gas, not protect the environment. They argued the act empowers the agencies only:

to withhold issuance of a drilling permit to prohibit waste which is unnecessary to the production of oil and gas. The statute, therefore, would impliedly protect any and all other waste, no matter how serious, if necessarily incidental to the production of oil and gas. According to the [oil company], the clear import of [Act 61] was not to conserve the environment in general but to conserve only oil and gas so that they are efficiently extracted.

The court rejected this and again affirmed denial of the permit. But among the seven justices there was no majority opinion. A three-member plurality noted the pre-1973 definition of “surface waste” but declined to rely on it, or its inclusion of the phrase “as those words are generally understood in the oil business.” Rather the plurality focused on “waste” in its general “ordinary” meaning and said waste:

includes any spoilation or destruction of the land, including flora and fauna …. Serious damage to the wildlife of Corwith 1-22 resulting from oil drilling is spoilation or destruction…. Conservation should not be read to apply only to the efficient extraction of oil, but should include the efficient extraction of oil which simultaneously conserves the other natural resources (flora and fauna) of the state.

To the operator’s contention that at the time it applied for the permit no rules or regulations existed which prevented unnecessary destruction of wildlife, the three-member plurality answered Act 61 required the agencies

to prevent waste, including serious or unnecessary damage to or destruction or wildlife, even in the absence of specifically promulgated rules and regulations.

A concurring justice said simply he would have affirmed the reasoning of Court of Appeals. That made four justices for denial of the permit, albeit with differing rationales.

The three dissenting justices argued that no waste within the meaning of Act 61 had been established, because the operator had acquired a mineral lease from the state and intended to exercise it prudently and carefully; and the primary purpose of Act 61 is conservation of oil and gas to assure maximum production. As to waste in its “ordinary” meaning, highlighted by the plurality, the dissenters answered:

Although use of the surface of the land by the lessee [oil company] results in death and injury to wildlife belonging to the lessor [landowner], such use is not waste within the “ordinary meaning” of that term if it is reasonably necessary for oil and gas operations. A lessee [oil company] does not abuse or misuse the estate granted when it carefully and prudently exercises the rights specifically granted to it.

There being no majority opinion, the Michigan Oil decision is not a binding precedent. But the 2014 decision of the Court of Appeals in Schmude Oil v DEQ, another Pigeon River case, was unanimous and binding. Schmude Oil held (without citing Michigan Oil):

The language in NREPA that deals with oil and gas production seeks a balance between Michigan’s interest in protecting the environment and its interest in harvesting valuable hydrocarbon resources. [Construction of Part does not express], as petitioners argue, a clear public policy favoring drilling.

The dissenters in Michigan Oil had given a nod to the environment: they recommended a remand to consider the facts under a separate law, the 1970 Michigan Environmental Protection Act (MEPA). MEPA, which our 1963 constitution required the legislature to enact, protects “air, water, and other natural resources and the public trust in these resources.” Under MEPA courts have overturned DEQ oil-gas permits.

But Schmude Oil and the other judges and justices in Michigan Oil reasoned solely from the language of Act 61.

Compulsory pooling: a practical effect of “Construction of Part”

Apart from Act 61’s overall ideology, there is one area where the Supervisor has held that fostering and maximizing production has an explicit effect on decisions: compulsory pooling — also known as statutory pooling — of unwilling interest owners. Act 61 says this type of pooling is allowed where

the smallness or shape of a separately owned tract or tracts would … otherwise deprive or tend to deprive the owner of such a tract of the opportunity to recover or receive his or her just and equitable share of the oil or gas and gas energy in the pool.

The state compels owners into pooling only after voluntary pooling has been attempted and failed. Jerome Maslowski observed in his 1970 article: “If a land owner does not pool voluntarily, he usually is subject to a penalty.”

Petition of OIL Energy Corp (Kearney Township Antrim County) was a DEQ pooling decision in 2011. In a 1454-acre unit, owners of 144 acres had declined to lease to the oil company. Assistant Supervisor Harold Fitch gave three reasons for compelling pooling and allowing horizontal drilling under the land of the declining owners. The first reason of course was just and equitable sharing cited in the above-quoted pooling subsection of Act 61.

But that subsection does not reference Fitch’s other two reasons: (a) “prevention or minimization of surface waste by fewer surface locations” and (b) “the ultimate recovery of natural gas can be increased and drilling through unleased tracts will assist in avoiding the drilling of unnecessary wells.” The two are inspired by the Schmude Oil view of “Construction of Part,” in seeking to balance protection of the environment and maximization of hydrocarbon resources.

Compulsory pooling means that mineral owners of land in an oil-gas pool – including those who oppose oil and gas on principle and don’t want the money – have no option but to surrender to a profit-making private industry. This was what happened to pooled oil-gas opponent Lorie Armbruster in Washtenaw County, cited by the Ann Arbor News in July 2013:

With horse pastures, a hay field, a garden and woods on her own property, Armbruster said she enjoyed the farm smells and activities nearby. Cow manure doesn’t bother her, she said, and the rumble of tractors and farm equipment was a comforting sound.

The addition of drilling rigs — 24-7 operations for about a month to install a new oil well across the street — and the associated large trucks carrying gravel for new roads — have turned her agricultural haven into an industrial site, Armbruster said.

A flare installed at the oil well across the street to burn off natural gas that can’t be captured from the well has also proved to be the biggest nuisance, she said. The smell of gas burning wafts into her home if the wind is blowing from the southwest —causing her to shut her windows and stay indoors.

“It’s farmland and their property and they were allowed to do whatever they wanted to it,” Armbruster said of her neighbors. “And we were very good friends with them so I didn’t say anything … I didn’t complain and once the flare started I still didn’t want to complain — but we’ve been suffering and other neighbors too — and it’s like, what can you do? It’s there; it’s there legally.”

In addition to the gases being released through the flare, Armbruster said she’s concerned for the future safety of her water well in her front yard should drilling activities or spills from crude oil transportation contaminate it.

In answer to those like Armbruster who have to “accept oil or gas development which they oppose for economic, environmental or aesthetic reasons,” James R. Neal, a past chair of the State Bar Oil-Gas Committee, argued in the Michigan Bar Journal in 1999 that compulsory pooling is successful:

Michigan’s declared policy is to foster the development of its oil and gas natural resources “with a view to the ultimate recovery of the maximum production of these natural products.” Those who want to capture the oil and gas beneath their land are entitled to do so, but their efforts are subject to Michigan’s declared policy and regulatory implementation of that policy.

…

The role of compulsory pooling in this regulatory scheme has been to preserve drilling units. The practice successfully balances the rights of those desiring to develop their oil and gas interests against the wishes of other owners who either oppose development altogether, or who oppose development on economic terms other than their own.

Neal conceded that no published Michigan court decisions address the constitutionality of compulsory pooling, but argued it is like zoning. He noted a 5-4 Oklahoma decision, Palmer Oil Corp v Phillips Petroleum Co, which upheld the constitutionality of a pooling statute like Michigan’s, in 1951.

But does Palmer Oil address Armbruster’s concerns? It involved the large 3700-acre “West Cement Medrano” unit in Caddo County, an area very different from hers. There were about fifty wells producing oil and gas on 72 separate ownership tracts with several hundred royalty interest owners at the time of the protested pooling order, while additional wells were in the process of being drilled. The object of the Oklahoma pooling statute was

that a greater ultimate recovery of oil and gas may be had [from the unit], waste prevented, and the correlative rights of the owners in a fuller and more beneficial enjoyment of the oil and gas rights[] protected.

The statute allowed a majority of the interest holders to initiate a compulsory pool.

The objectors were lessors, lessees, and royalty owners. They made no environmental arguments, such as danger to animal or plant life, water or air quality, or climate.

As to any objector who simply didn’t want to participate in the oil business, the four dissenting justices in Palmer Oil noted their opponents’ astonishing answer: “the taking resulted in no loss to the owner, but, on the other hand, resulted in gain to him.”

The dissenters, citing federal precedent, taking care not to dispute principles of well spacing and proration, and noting that issues of water drainage districts are not analogous, labeled regulation by a majority of interest holders over the affairs of an unwilling objector “obnoxious.”

Michigan should stop fostering the oil-gas industry

Like Charles O. Galvin, the state of Michigan wrongly assumes that for everyone – landowners, investors, and operators – “the underlying motivations in each case are the same”: acquisition of “usable economic wealth” with minimum tax, litigation, and business costs.

Because DEQ fosters the industry, it is a captured agency — one that advances the concerns of the special interest group it is charged with regulating. Capture is normally frowned on and the captured regulators often deny it. But far from denying, the Michigan legislature is proud of it.

The obvious first option for reversing it of course is political action and lobbying of elected decisionmakers. But with current officeholders there is little hope. On February 13, 2018, Governor Rick Snyder keynoted an all-day “Governor’s Summit on Extractive Industries” in East Lansing. MOGA announced the goal was to promote and showcase extraction companies. Over 200 attended. For legislators and staff, the $50/plate event and lunch were complimentary.

Leading committee members of the House and Senate opened the meeting. It was co-sponsored by MOGA, whose chairman Joel Myler sat on the opening “extractive industries 101” panel. Harold Fitch, the assistant Supervisor of Wells, sat on the second panel. Attendees watched this video.

Four days earlier, this writer contacted the governor’s office through his website, provided the link to this article as originally posted on February 3, and asked this question:

Do you agree that production of oil and gas exacerbates global warming which can lead to world-wide catastrophe, and if so how do you square that with Michigan’s policy expressed in MCL 324.61502 that DEQ regulators are to ‘foster’ the oil-gas ‘favorably’ and ‘maximize’ oil-gas production?

He has not responded.

More recently, newly-elected Governor Gretchen Whitmer established an Office of Climate and Energy. But as of May 2020, the climate page of the OCE website lists no regulations, policies, or laws for monitoring or limiting methane or CO2 emissions.

The more promising option is to call public attention to the fostering/maximizing issue and then for public action. The issue dovetails with the related issue of fracking — the modern version of what the Saginaw developers did with exploding nitroglycerine in the 1920s. Today the lion’s share of US climate-changing oil-gas production is developed with fracking completion methods, particularly in horizontal wells.

Polls show majorities oppose fracking nationally and in Michigan both among local officials and voters.

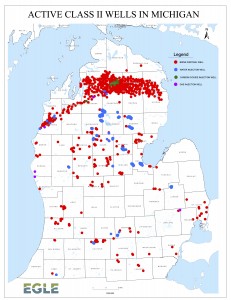

Our state has a long history with vertical fracking. As the Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy explained in 2014 it has been used in Michigan since the 1940s:

However, this earlier hydraulic fracturing was undertaken with vertical drilling only and relatively small volumes of water usage. More controversy has grown recently around the use of high-volume hydraulic fracturing, which uses horizontal drilling to expand the underground area that can produce gas or oil, but which also requires much higher volumes of water, and produces higher volumes of used “fracking fluid” mixtures that must be disposed of somewhere. All of these factors have raised potential health and environmental concerns. In Michigan, the issue of fracking has seen a marked increase in attention.

Since 2015 the Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan (CBFM) has undertaken a statewide ballot initiative to ban horizontal fracking and acidizing and their wastes. The initiative is known chiefly for that language. It would also include the substances involved in horizontal fracking in the definition of prohibited waste. The exact language is here.

The initiative is motivated by public health and environmental concerns in addition to climate.

But a sleeper issue of the initiative has drawn little public attention. In the opinion of this writer it is the more important issue. The initiative language would amend “Construction of Part” to delete the fostering/maximizing policy. As amended the statute would say:

It has long been the declared policy of this state to foster conservation of natural resources and to provide for the protection of the air, water, and other natural resources from pollution, impairment, and destruction. In past years extensive deposits of oil and gas have been discovered that have been extracted using wells through which oil or gas flowed naturally or was pumped to the surface. The recent uses of high intensity horizontal hydraulic fracturing and acid well stimulation and completion treatments are different and typically include injections of large amounts of water, solvents, acids, and other chemicals to fracture or dissolve underground formations horizontally, the consequences of which pollute, impair, and destroy our water resources, land, air, climate, and public health. The interests of the people demand that the exploration of oil and gas shall not be done at the expense of the natural environment and human health. It is accordingly the declared policy of the state to protect the interests of its people and environment during gas and oil development. This part is to be construed liberally to give effect to sound policies of conservation and the prevention of waste and exploitation, and to protect water resources, land, air, climate, human health, and the natural environment.

The language would not change the subsections of Act 61 which declare unnecessary wells as “waste.” The statute would continue to provide for proration and drilling units.

Unitization would not be affected.

Nor would there be changes regarding compulsory/statutory pooling. The process would continue as before, with decisions based on owners each getting a “just and equitable share” of the oil or gas. The Supervisor could continue considering prevention of waste.

But instead of fostering the industry and maximizing production, decisions under Act 61 would now highlight values consistent with the Michigan constitution:

The conservation and development of the natural resources of the state are hereby declared to be of paramount public concern in the interest of the health, safety and general welfare of the people. The legislature shall provide for the protection of the air, water and other natural resources of the state from pollution, impairment and destruction.

This is apt, given that the Supervisor of Wells is the Department of Environmental Quality.

More generally, a new view would replace the old one in all manner of DEQ judgments and decisions ranging far beyond compulsory pooling.

Should the CBFM measure succeed, the governor could not veto it, nor could the legislature amend or repeal it except by a ¾ vote in both houses.

By thinking globally and acting locally, Michigan will have made its own contribution to forestalling or preventing climate change.

Notes, legal sources, photo credits

As mentioned above, IOGCC has 38 member states. Most or all of them have policies embedded in their statutes and regulations similar to Michigan’s “Construction of Part.” An article similar to this one could be written for each state, using sources arising in that state.

Underlinings in quoted materials above are added. Footnotes in quoted materials are omitted except for the “in trust for the public” paragraph which was in a footnote of Ford’s, quoting another author.

Quoted legal articles:

- Donald H. Ford, Controlling the Production of Oil, 30 Michigan Law Review 1170, 1171-78, 1178-1201, 1202-06 (1932).

- Charles O. Galvin, Developing an Oil and Gas Jurisprudence in Michigan, 7 Wayne Law Review 403, 403 (1961). A scanned copy may be obtained from the WLR managing editor.

- Boice Gross, Michigan’s Legislation Governing Oil and Natural Gas, 10 Michigan State Bar Journal 193, 194 (1931).

- Jerome Maslowski, Government Regulations Many and Varied, 49 Michigan State Bar Journal 50, 50, 52 (1970).

- James R. Neal, Compulsory Pooling Promotes Conservation of Michigan’s Oil and Gas Natural Resources, 78 Michigan Bar Journal 158, 158, 161, 162, 163 (1999).

- William Reid Ralls, Oil and Gas Regulation: An Overview, 68 Michigan Bar Journal 14, 16, 17 (1989).

- James A. Veasey, The Law of Oil and Gas, 18 Michigan Law Review 445, 445 (1920).

Photographer credits: unknown. The Clarke Library notes that almost all its photos were taken from the files of the Michigan Oil and Gas News (MOGN) or the private collections of two long-time editors of the MOGN, Norm Lyons and Jack Westbrook.

casing failures, and citizen complaints. None of it is there. The public, and the EPA, know NOTHING about whether the State is properly enforcing the laws and actually protecting Michigan’s underground drinking sources! Yet, EPA has approved Michigan’s application.

casing failures, and citizen complaints. None of it is there. The public, and the EPA, know NOTHING about whether the State is properly enforcing the laws and actually protecting Michigan’s underground drinking sources! Yet, EPA has approved Michigan’s application.

Beckett worked to get Attorney General Frank Kelley to issue an opinion on the new law. He did in 1974, but too late to affect her Committee’s campaign.

Beckett worked to get Attorney General Frank Kelley to issue an opinion on the new law. He did in 1974, but too late to affect her Committee’s campaign.

There is growing alarm in Michigan by the increased number of proposed natural gas power plants that will burn natural gas (from fracking) in order to make electricity. If any of these are successful in being built, they doom Michigan to being dependent, for decades upon decades, on more fossil fuels and sustained fracking, and untold amounts of frack wastes endangering the health of future generations. Untold amounts of water used for fracking . . . to find natural gas . . . to burn . . . to make electricity. It’s not sustainable, and it’s not going to save our water or the climate.

There is growing alarm in Michigan by the increased number of proposed natural gas power plants that will burn natural gas (from fracking) in order to make electricity. If any of these are successful in being built, they doom Michigan to being dependent, for decades upon decades, on more fossil fuels and sustained fracking, and untold amounts of frack wastes endangering the health of future generations. Untold amounts of water used for fracking . . . to find natural gas . . . to burn . . . to make electricity. It’s not sustainable, and it’s not going to save our water or the climate.