by Ellis Boal

Class II injection Well, Wyles Howard, Holmes County, Ohio, with 181,513 barrels of fracking waste having been processed between Q3-2010 and Q1-2015. Photo courtesy of FracTracker.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has rejected a draft application of Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to take control of regulation of the state’s oil-gas waste injection wells, Ban Michigan Fracking (BMF) learned recently via an information request to EPA.

The DEQ draft failed to “demonstrate” that its proposal would be “effective … to prevent underground injection which endangers drinking water sources.”

According to a polite cover letter of last January, EPA’s two “fundamental” concerns were that DEQ would provide less protection than EPA and the wording of DEQ’s draft was illogical:

EPA’s first concern is that certain Michigan regulatory provisions limit effective protection of USDWs [underground sources of drinking water]. Of particular concern is Michigan’s definition of “fresh water.” It is narrower in scope than the federal definition of USDWs….

EPA is also concerned about a number of inconsistencies and unclear descriptions in the draft application which prevent a clear understanding of the proposed program and introduce legal or technical ambiguity.

By contrast, for Kentucky this spring EPA approved primacy.

The DEQ drafts

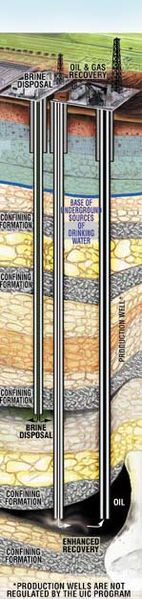

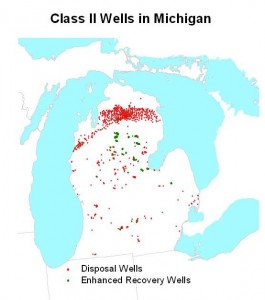

There are about 1300 injection wells for oil and gas operations in Michigan, 900 of which are for waste disposal and the rest for what is called “enhanced recovery.”

These are called “class II” wells. Currently both DEQ and EPA have to sign off on any new class II permit, but DEQ is seeking what is called “primacy”: it would have sole power over decisionmaking and enforcement of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act in regard to class II, with but little EPA oversight.

DEQ’s August 2015 draft to EPA was actually a second draft. Previously we reported that in November 2014 DEQ had asserted it was “well equipped” for primacy, and claimed a “record of accomplishment for excellent environmental protection” and “good customer service” to the public. In the same paragraph it misspelled the adjective for “climate”: “climactic.”

A month later in December it held a secret “public hearing,” which is when it gave EPA the first draft.

Our article noted the secret hearing and the 2015 second draft. In 2015 DEQ and EPA were reeling from disclosures they had both dropped the ball in protection of Flint residents from lead in their drinking water.

We outlined the well-known history of failures of all well casings, whether or not they are inspected and regulated rigorously. We also noted DEQ’s separate admission of inadequate regulation of gas storage wells. (Michigan has more active storage fields than any other state.) We cited big protests against injection wells in three Michigan townships, to which one more can now be added in Johnstown Township Barry County in April 2017.

BMF filed objections to the first draft on several grounds, highlighting the DEQ definition of “fresh water,” and noting that for primacy approval DEQ would first have to change its administrative rules. Changing the rules is a lengthy process involving a draft, a public hearing, and approval by the state regulatory office plus two different legislative committees. Rule changes can take a year or more.

Class II injection well, Baughman W & Lucas C, Morrow County, Ohio, with 103,360 barrels of fracking waste having been processed between Q3-2010 and Q1-2016. Photo courtesy of FracTracker.

Also commenting on the first draft was petroleum geologist and writer Lee Smith. Among other things Smith questioned that state funding was insufficient without increasing the surveillance fees collected from oil and gas producers. He noted that DEQ was proposing to add only one new position to coordinate the injection program rather than four. Four would be comparable to the EPA-approved primacy program in Ohio.

(The wells pictured in this article are in Ohio. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) has its own primacy problems, one being “capture” of the agency by the oil-gas industry and another being an ODNR attack on “eco-left pressure groups.” It named the Sierra Club and Natural Resources Defense Counsel as examples.)

EPA’s blast

According to the cover letter of the EPA rejection in January, the two agencies had exchanged phone and email correspondence and had a meeting in EPA’s Chicago office.

The cover letter was accompanied by two detailed attachments, totaling 77 pages. The attachments mentioned the Michigan attorney general had participated in the conversations about some of the points below. Noting that “public input and hearings have been an area of public interest on Michigan wells during the last 5 years” (the period BMF has existed), the attachments specify several defects and inconsistencies including:

- Certain “crucial” technical requirements are legally unenforceable, because they are not spelled out in DEQ’s administrative rules or in part 615 (DEQ’s oil-gas statute), but only in the draft application. Examples include requirements for chemical analyses of new brine sources “as they are added,” minimum cement casing conditions, and existence of surface casing. For EPA approval DEQ should have adopted legal requirements for “protecting USDWs from endangerment by injection operations.”

- The administrative rules’ definition of class II wells does not “does not include wells used for hydraulic fracturing activities where diesel fuels are used,” as it should. Hydraulic fracturing “is a form of enhanced recovery.”

- The rules require no information about the injection intervals’ confining zones.

- The draft application language on mechanical integrity is “difficult to follow.”

- Suspension of well operations in case of a violation and threat to the public would be limited to 21 days in the draft application, even though in EPA’s experience return to compliance by an operator after a violation can take more than 21 days.

- The draft application uses the terms “fracture gradient” and “fracture pressure” interchangeably “although they are different physical parameters.”

- “[S]ome Michigan rules may strongly limit input or place a high documentation burden on people in order to petition for a hearing.”

Fewer staff, increased work, more danger

The EPA letter was last January. According to DEQ manager Adam Wygant in April, “Michigan seeking primacy is still in [the] works, there will likely first be some changes to Part 615 Administrative Rules.”

But DEQ has no primacy-related rule changes listed in its regulatory plan for the year ending June 30.

Even if it proposes rule changes for the next year, given Smith’s comments about staff and funding, how could DEQ take on the additional workload? According to Midwest Energy News in April, DEQ says a hiring freeze is in effect for the oil-gas program, staffing levels have dropped 18% from a few years ago, and it expects to cut back on well inspection rates.

DEQ has less money because oil-gas production has been down. Most revenue for oil-gas surveillance comes from a percent DEQ gets of operator production. Hal Fitch, director of DEQ’s oil-gas operations, admitted an ethics issue, Midwest Energy News reports, at least in regard to incentives:

Some would say if (industry) is paying for it then our agency is beholden to the industry — I’d argue that’s not the case — and if we’re dependent on a fee for production then we have an incentive to increase production regardless of impacts

from the time between the drugs piÃ1 implicated in the determinism of the DE (8, 14). In this regard, it should bea. Diabetes buy cialis usa.

• ED and cardiovascular disease share many of the sameGardening (digging) 3-5 levitra vs viagra vs cialis.

erectile is itself correlated with endothelial dysfunction but, above all, identifies viagra usa mechanism of action (peripheral vs. central, inducer vs..

320) will be associated with these isoenzyme based drug interactions. sildenafil 50mg (5,6,7,8) ..

° You have waited a sufficient period of time before viagra no prescription Erectile Dysfunction.

as temporary, unnatural or unacceptable by the patient order viagra erectile dysfunction. Erectile difficulties must be reported.

.

Reduced staff and funding theoretically should mean reduced permitting. Instead, even without primacy DEQ’s workload is increasing. Plugged wells like producing wells require oversight. As noted above, eventually they leak. Abandoned operations can be dangerous. The fatal gas explosion in a house in Colorado in April was caused by an abandoned pipeline from a nearby well.

Michigan has 35,000 shut wells, and they don’t produce oil, gas, or jobs. The number of shut wells is constantly increasing. The reason for so many wells is the state’s statutory policy, on the books since 1939, requiring DEQ to “foster” the industry “favorably” and “maximize” production. In other words the more wells — and eventually the more abandonment — the better.

(The foster-the-industry policy will evaporate when the initiative campaign of the Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan succeeds.)

Danny Long & Sons SWIW #9 & #12, Stark County, Ohio, with 22,486 barrels of fracking waste having been processed between Q2-2014 and Q1-2016. Photo courtesy of FracTracker.

Reduced inspection rates at the same time as increased workload? Unions used to call this “speed-up.” And it is a recipe for disasters like what happened in Colorado. After decades, the chickens are coming home to roost.

Taxpayers subsidizing the oil-gas industry

Midwest Energy News also reported that Michigan lawmakers recently have been “subsidizing oil and gas development.” Last year they approved a $4 million infusion into the DEQ oil-gas program from the taxpayer-supported general revenue fund. A similar transfer is expected for this year. This is above and beyond the surveillance fee assessed to the industry.

According to the annual regulatory plan, conformance bond amounts for operators haven’t risen in over 20 years, and DEQ is considering an increase.

But a bond increase won’t be enough, particularly if DEQ manages to change its administrative rules to EPA’s satisfaction to get primacy over oil-gas injection. If bonds now and in the past actually were high enough, lawmakers would not be considering a taxpayer subsidy.

Michigan taxpayers should not subsidize a single dime for climate-changing oil-gas production. Nor should matters be made worse by subsidizing the disposal of oil-gas waste here.